Today is the final part of a three-part article series about implementing and managing resources in your game. If you haven’t been following along, check out the first two articles in the series. Part one discussed the nature of resources in games, and went into some detail about different types. Part two dove deep into the implementation of resource systems.

Today’s subject is maybe the most important one in the series: making it fun for the player.

Here’s some required reading (okay, maybe “heavily suggested”): Player Psychographics.

Why? Because it’s all about understanding the idea of fun. What is fun? Everybody has a different definition. The Player Psychographics article goes into detail about how different types of players have fun—and how to design your game in ways that will ensure there’s something that appeals to everybody.

I’m not going to be expanding on the ideas of Timmy, Johnny and Spike in this article—but it’s a useful baseline to have when evaluating what different players would describe as fun. Some players will never be satisfied with managing their resources—others can’t get enough of it. When dealing with something potentially polaziring like resource management, the important balance comes in offering the player a choice.

Encouraging Fun

I don’t need to say again that different people will find different things to be fun. But here’s something that’s true for everybody: something is fun if they want to do it. It’s an idea that a lot of game designers don’t understand very well. Many even fall into the mindset that its their job to prevent the player from doing what he wants to do—that the purpose of the game is to make the player fight to earn his enjoyment.

Instead, the game should be fun the whole way through. If you find that the player enjoys doing something in the game, encourage it! Reward the player for doing what he wants to do anyway.

Here’s an example, in the context of our subject of resources.

Let’s say that your game has a mechanic where your player characters take damage if their MP is low. On one level, some designers might find that kind of mechanic interesting—they’d say that it adds a new level of strategy to battles. And it probably does. It also clashes with the whole point of MP itself. The typical RPG battle system expects and encourages the player to use their character’s skills. By creating a drawback when the player does just that, it makes the player not want to use his skills in the first place. Not only does he have to manage his MP in the regular way, but he has to worry about taking damage from using his regular special skills. As a result, the mechanic is actually punishing the player for doing something that would otherwise be fun.

Why not do the exact opposite? Give the player a bonus when he depletes his MP. Maybe it will instead recover some of his health. Imagine a tight boss battle, but you know that if your character is close to dying—but you manage your skills in a way that you use a sweet magic attack and then recover the character. The amount of resource management that the player does in this situation is similar to when he would be taking damage, except this time he’s much more willing to do it because it benefits him. It doesn’t feel like a punishment, but a goal for him to work towards.

The example might be a little extreme (the best examples are)—but it illustrates a design concept that really enhances the amount of fun your players have while playing your game. There’s no downside to it for the player (freeing him up to find challenge in other aspects of the game instead of fighting against the gameplay itself). “All-upside” mechanics don’t punish the player. Of course, not every mechanic can be all-upside; but if you approach your game’s core mechanics with a mindset that rewards the player, your game will appeal to a much wider audience and you’ll avoid a lot of ragequits.

So how do we apply all-upside design into resource gameplay while keeping it balanced?

Making Conversion Fun

I mentioned in part two that a key aspect of resources in game is conversion. In fact, it’s the entire purpose of having a resource system in your game. The purpose of the player’s resources is for them to be converted into something that advances the player through the game.

Example: in an RPG, a player has gold. He uses it to buy new armor at a shop. Simple. And also kinda boring. Maybe it’s not unfun, but it’s certainly not exciting. So how do we inject that element of fun into this kind of system?

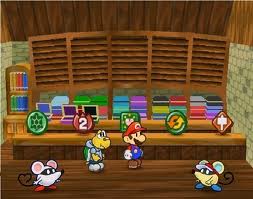

One way to do it is by adding more interactivity. Spice up your shops so they’re more than simple menu screens. In the spirit of rewarding the player, give him a bonus whenever he spends X money at a shop; maybe the shopkeep gives him a freebie or some store credit. It works in the real world, doesn’t it? Or take it in another direction—avoid the menu screen by having an actual shelves that the player can browse. Or hell—do both. Paper Mario nails it when it comes to shops that are somehow fun to shop in.

It’s not a highlight of the game—don’t get me wrong. You don’t think “sweet! it’s time to shop!”. But they are fun in the sense that they are so seamlessly woven into the game without feeling like you need to spend time in menus. You go in, buy your stuff (while continuing to move your character and interact with objects, instead of a menu), and continue on your adventure.

The same approach of adding additional interaction can be applied to other sorts of resource conversion. Crafting systems are becoming increasingly popular in games. Maybe your game could benefit from some sort of minigame—if the player does a good job, the item he is crafting might get some sort of bonus. Of course, I would suggest that you don’t punish him for doing a poor job. Having the raw resources in the first place should be enough to get the minimum. This way, he won’t feel forced into a minigame if he doesn’t want to. But the option is there, to add gameplay to resource conversion as well as an extra upside for the player.

Little things can make the conversion a lot more fun, even if they aren’t directly related to the gameplay. The right sound effect or animation can go a long way.

Of course, I would also note that adding too much extra complexity can bog down your game with useless features. Keep it clean.

Another way to make resource conversion more fun is to ensure that the player’s profit is significant. This is something that—as you can probably tell from the rest of the article—I think should happen a lot more often in games. When the player trades in his twenty fetch-quest items, he should get a reward that far outweighs the value of those items—and something that definitely makes him feel like it was worth his time to collect them.

Consider two scenarios. In the first, the player spends half an hour collecting sea shells. He brings them to a hermit NPC, who gives the player money in return. In the second scenario, the hermit instead teaches the player a unique skill that he can use in battle.

The first scenario is boring. It’s a conversion of one resource into another—but the second resource is one with the only purpose of being converted again. On top of that—it’s likely that the gold isn’t worth the time the player spent collecting the sea shells in the first place. He was likely getting gold from monsters anyway, while he was searching for the items. Gold is a weak reward, and will make the player feel like his time was wasted.

However, if the reward is really sweet—suddenly that conversion is a lot more fun. If he gets a cool skill that he can’t get any other way, it becomes exciting to trade in those sea shells.

The bigger the reward, the more fun it is for the player. Don’t be afraid to give the player the better side of the deal—in fact, it should be that way by default. Your player is the one who gets the value. If he feels like he’s getting more value than the effort he put in, he’s having fun. You want him to think “yeah, that was worth it!”

Making Management Fun

Some players enjoy managing their resources. Some hate it. In lots of games (entire genres), resource management is the core gameplay mechanic. In others, it just gets in the way. Think about how much resource management your game actually wants.

Let’s take a look at Cookie Clicker. It’s become a really popular game, and it’s entirely about resource conversion and management. It’s a great example of the core ways in which resources can become fun: it creates a strong sense of player progress. That’s exactly why it’s so addicting. The more cookies you have, the more cookies you can make. You start off by making a single cookie with each click of the mouse, but soon enough you are making ten million cookies a second without clicking at all, by managing your ever-increasing army of resource-creating units.

The reason that Cookie Clicker is fun is because the management of your cookies leads to tangible progression. The player can see numbers flying across the screen—at the beginning of the game, you see a 1 every time you click. Soon enough, you’re seeing numbers in the billions flash every tenth of a second, and your totals just keep going up and up and up.

Resource management is boring and unfun if it isn’t used in a way that enhances the player’s sense of progression.

What kinds of things are common in resource management in games? In RPGs in particular (since RPG developers are most likely to be reading this article)?

- Managing resource limits

- Upgrading/breaking down resources (conversion)

- Comparing stats

- Discarding resources

- Using resources

Conversion was largely covered earlier, and using resources was covered in part two. When the player is managing his resources (in RPGs), he’s spending most of his time comparing them and maybe discarding useless ones (particularly if there is an inventory limit).

All of these things are useless micromanagement unless they contribute to the forward momentum of the gameplay. In fact, unless the player is profiting from these interactions (by leveling up, acquiring new items, or progressing the game itself)—these things, more often than not, actively detract from the gameplay experience.

And the last thing that you want to do is detract from the gameplay.

Every element in your game, even—especially, potentially tedious things like resource management, should contribue to the forward momentum of the player’s progress. That’s how it becomes fun.