Howdy! I’ve been playing and reviewing RPG Maker games for over a decade, and it’s an unfortunate fact that very few of them stand out. It’s rare for an amateur RPG to feel original—and ever rarer to find one that really offers a unique experience. Most games are simply forgettable.

The best way to ensure that your game is memorable is to create a unique identity for it.

This article is a follow-up to my previous article about game design, Fuck Your Features. In that article, I talk about how to recognize and cut down on excessive features that may harm your game—in this article, I’m going to discuss ways to isolate and implement positive features in order to create a unique identity for your game.

Gameplay Identity

What do I mean by “identity”? One dictionary entry defines it thus: “the condition of being oneself or itself, and not another“. In other words, something with an identity stands on its own. If we apply that concept to your game, its about all the aspects of the game that combine together to form a cohesive and one-of-a-kind experience.

There are plenty of ways to create an initial identity for your game—an original graphical style, a resonant setting, a unique cast of characters—but at the core there is an undeniable truth: a good game needs to be fun to play. So while it’s one thing to make your game look unique, the gameplay is responsible for making it feel unique. Gameplay is the glue that holds all of these elements together, and truly defines an identity—it is the responsible for the experience of your game.

If you want to give your game a unique gameplay identity in order to set it apart from other RPG Maker games, you don’t need to cram it with features—in fact, that will have just the opposite effect: if your game seems unfocused, then it won’t be memorable.

If you need your game to stand out, don’t load it with every feature you can think of. That approach will only water down the elements of the game that make it truly unique. Find an important core feature that is strong enough to become the backbone of your game—and build off of that to create a unique gameplay identity.

Paper Mario’s titular gimmick allows for a variety of unique mechanics that feel natural and connected.

In my previous article, I talked about narrowing down your game’s features to whats necessary. A couple of core gameplay features can go far—find a unique mechanic that you can experiment with—something that you can build on top of. A good mechanic is one that can continually present new challenges to the player without changing the fundamental way the player approaches the game.

Let’s look at an example that is possible in RPG Maker—imagine that your game’s world makes use of terrain-based magic. Skills might vary in effect and intensity based on the location in which the battles take place. One character may be a fire mage, and his magic gets a tremendous boost in that volcano dungeon (you know the one). Maybe, as long as the part is in that area, the fire mage has access to a powerful ability that he wouldn’t be able to use elsewhere—or maybe he gets a power boost or something like that. Another character, a water mage, finds that her abilities are weakened in that same environment. This is a mechanical concept that can be introduced easily enough, and allows for a strategic backbone that links your game’s battle system to the map surroundings.

As the game progresses, that concept should evolve in a natural way that doesn’t break the concept. Create locations that present new challenges to the player in ways that work with the mechanic: a desert region might weaken the magic for all the characters, a dungeon might have a switch that changes it from a fire temple to an ice cavern. Allow other elements of your battle system to build on the idea—a specific piece of equipment might increase its bearer’s speed in grassy terrain, another might ignore the negative effects of an area. Then push it even further: the final party member is a “terraformer” mage, whose special abilities can actually change the terrain of the battlefield, allowing the player to finally take control of the mechanic that has been so prominent throughout the first half of the game.

No matter what game mechanic you choose, allow it to influence all aspects of your game, and design your features in ways that continually challenge the player to work with and around that mechanic. Let it grow over time, and build other features into that core mechanic. When a player thinks about your game, he’ll remember the way that your mechanic influenced the way the game felt.

The Familiarity of Genre

Once you’ve established a core for your gameplay, there’s no shame in falling back to classic game tropes. That’s what genre is: a framework that allows the player to feel comfortable in the ways he explores your game’s unique features. Your game’s identity can be an exciting twist on the familiar aspects of your genre.

Because we’re primarily talking about RPGs here, let’s look at an example that puts a unique spin on the RPG genre without betraying the elements that make it work. I’m talking about Pokémon—of course.

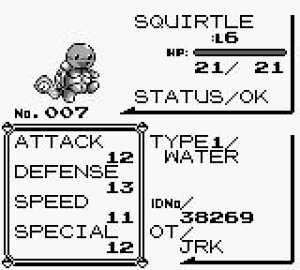

Any RPG player can make sense of the stats screen in Pokémon, even though it doesn’t use a traditional party structure.

The single core element of the game—the identity of the game—is in the system of catching monsters and creating a team out of of them. The beauty of the system lies in the way it overlaps so perfectly with familiar RPG mechanics: the turn-based battle system, the rock-paper-scissors aspect of elemental attributes, the increase of stats based on battle experience. Recognizable RPG concepts like “hit points” and “potions” work exactly as the player expects them to, while catching monsters in “pokéballs” or storing them in “Bill’s PC” are unique to the game. The result is a perfect balance—a unique gameplay experience that doesn’t seem intimidating.

Even more, other classic RPG mechanics are built into the core identity of the monster-catching system. Hidden Machines give skills to the player’s team members that allow him to progress: where other RPGs might require the player to find power gauntlets to move obstacles, Pokémon has the player to teach that special ability to a monster. Instead of a boat to allow the player to cross water, the special move “surf” lets the player ride on the backs of of his water-type pokémon.

To players familiar with RPGs, Pokémon is intuitive while retaining a unique and memorable core concept. Even if a player doesn’t have RPG experience, the existence of the genre creates a firm basis that doesn’t completely alienate him.

Take advantage of your game’s genre and the player’s familiarity with it. Not every trope is a cliché, and not every cliché is automatically bad. Design your game’s unique identity to work within your genre, and take it in new directions. Think about ways to tie familiar genre gameplay elements into the core identity of your game.

Mechanical Tone

When your core gameplay mechanics set a tone for your game, new mechanics must stay in line with that tone. Otherwise, you risk a disconnect that could cause the player to become confused or frustrated.

This isn’t to say that you can’t mix things up—you should! Variety keeps gameplay fresh. But be careful that you don’t stray far from the identity that you’ve created for your game.

It’s not easy to define what I mean when I talk about a game’s “tone”—it’s an intangible but crucial aspect of your game’s identity (note that I’m talking about tone in regards to gameplay, as opposed to a literary tone that would be a part of the script—although the latter can also play a vital role in establishing identity). It’s about pacing and immersion, about how your design presents challenges and teaches the player to handle them. It’s the way that individual elements of your game seem like they have something in common, even if they don’t.

I remember an RPG Maker game that I played once; it was a solid game with great dungeon design—but there was one game mechanic that appeared a couple of times that required the player to use the mouse. The entire game, other than those isolated puzzles, used only the keyboard. When the mouse mechanic was introduced, it felt awkward and out of place. This is an extreme example—one that breaks the rules set out by the game’s control scheme—but the lesson is simple: once you establish a tone for your game, breaking it can ruin a player’s immersion in your game world.

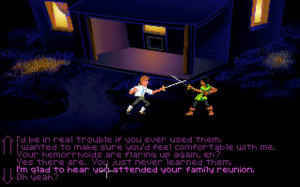

The Secret of Monkey Island found a creative and hilarious way to incorporate combat without breaking game’s thoughtful pacing.

Your game’s mechanics set the tone of your game. If your game’s mechanics teach a player to approach the game in a certain way, it’s important to stay consistent with that line of reasoning, or else the player can get confused or frustrated. When introducing a new gameplay element, consider the effect that it will have on the tone of the game. The mechanical tone of your game can change as the game progresses—but if it does, it needs to be in a natural way that doesn’t contradict what has come before.

Let’s look back at our example from before—the RPG that makes use of terrain-based magic. That mechanic has encouraged the player to think about battles strategically—he has been naturally trained to understand that the location of the battlefield changes the mechanics of the battle itself. Now say that you want to create a vampire boss who uses shadow magic. The player will naturally be looking for some kind of weakness that is tied to the arena of the battle—if there’s no way to exploit the environment, the player might feel that the vampire boss defies the tone established by the game’s central mechanic.

To make the vampire battle fit in with the mechanical tone, and the player’s understanding of the game, you’d want to incorporate some way that the terrain effects the battle. For example, perhaps there is a way for the player to light lanterns—and the vampire’s shadow magic is weakened as long as the environment is brightly lit. Not only does this addition connect the vampire to the central mechanic, but it increases the amount of strategy involved in the fight—which makes sense with the strategic pacing laid out by other battles.

Consistency matters. If you break it, you risk breaking the identity of your game. Don’t be afraid to push your game’s mechanics into new territory and challenge your player, but make sure that you stay within the boundaries of what you want your game to be.

At the end of the day, your game’s identity is what the player remembers about your game—what he takes away from it. And hopefully, that’s a fun experience.