Yo. Today I feel like talking about NPCs.

I’ve played a lot of amateur RPGs and nearly all of them feature the same copy-paste “welcome to this town” NPCs. Lazy game developers will treat NPCs like scenery—like they’re just a part of the map and not living characters. The strange part is that people know that these kind of NPCs are boring and lame, but they rarely take the time to flesh them out. Hopefully this article can help you come up with some great NPC ideas.

What is an NPC?

The simplest definition is obvious: NPC stands for non-player character.

However, that doesn’t seem to cut it with modern games. When we strictly follow the “non-player character” definition, a lot of central characters—like major antagonists—should be labeled as NPCs. And while that might be true from a technical standpoint, the modern usage of the term is a bit more specific: typically NPCs are the commoners who inhabit the game world without being caught up in the major events of the story. Plenty of people would argue that major story characters are NPCs, too—and I can’t disagree with that.

For the sake of this article, we’re not talking about those characters. I’m talking about the day-to-day people, the working class citizens who make your world come to life.

Making NPCs Memorable

Why bother? The player just wants to skip ahead to the next dungeon, right? Well—if your NPCs suck, of course they will. Here’s a problem: the player will only care about the NPCs if you give him a reason to.

The obvious reason for a diverse cast of NPCs is that it gives the world depth. People have personalities, and the more personality you can cram into your game world the better it will be. People have lives—people have jobs. If your NPCs seem to exist only for the sake of the player, then your game’s immersion factor is slaughtered. If the player can remember every person (or most people) that he comes across, the world feels so much more real. I would argue that every single NPC in your game needs something unique about him or her.

Consider that most RPGs have a “save the world” plot: these are the people who you are saving. These people are the reason that we want to defeat the evil sorcerer and save the planet. If you have no connection to these people, if you have no reason to care about them, the magnitude of your quest will be significantly lessened. I love the sequence that plays during the end credits of Ocarina of Time: you’ve succeeded in saving the world and all of the people that you have encountered along the way are celebrating around a bonfire. You recognize them, you know them—you’ve interacted with all of them on some level or another—and you feel like they know you too. You feel like you’ve genuinely succeeded in helping them. It’s a good feeling—it’s a great feeling.

It was all worth it for them.

Ideas and Examples

Let’s look at some memorable NPCs from Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda series and what we can learn from them.

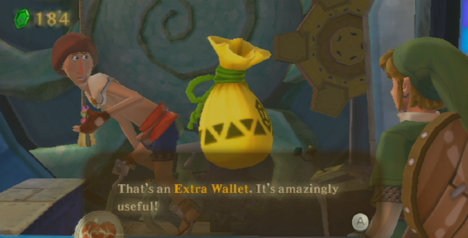

This is Beedle, who first appeared in The Wind Waker and most recently in Skyward Sword. In both appearances, he runs a specialty shop that sells unique items. Also in both appearances, he has a very distinctive appearance and personality (and voice—anybody whose visited his shop in Wind Waker will remember Beedle’s “thaankyouuu!”). In Skyward Sword, he’s given even more depth. For example, if you go into his shop but leave without buying anything, he’ll get mad and drop you out a trap door. On top of that, you can find him at home at night, where he seems to lose his distinctive accent and speaks completely differently when he’s “off the clock”.

Beedle shows us that:

- Shopkeepers can have personalities.

You’ll recognize this fellow; it’s Ingo from Ocarina of Time. He’s the scabby dirtbag who took over Lon Lon Ranch and tried to lock you up—until you escaped and rescued your horse, Epona. What’s cool about Ingo is that he has a full character arc: in the beginning of the game he is a lazy ranch hand, but after seven years pass he makes a deal with Ganondorf and takes control of the ranch (while Talon, the previous owner, is now found in a house in Kakariko). After the player puts Ingo in his place, he returns to being a ranch hand, humbled by the experience. It’s a simple arc for a simple character, but it’s enough to give him personality that makes him memorable and adds depth to the inhabitants of the world.

Ingo is proof that:

- NPCs can change over time.

Tingle! Tingle! Kooloo-Limpah! A lot of people hate Tingle, and though I don’t really understand the massive fanbase that he has acquired in Japan, I think he’s a fantastic NPC because he’s so recognizable. Lets ignore his gimmicky side games; Tingle was one of the most memorable NPCs from Majora’s Mask. He floated around on his bright balloon and when you popped it, he would be eager to sell you maps of overworld areas. He’s instantly recognizable for his uncomfortably bright clothing, insane personality and obsession with fairies. But more importantly, he has a family: the man who runs the pictograph contest will grumble about he is disappointed because his son is too old to be obsessed with fairies. It isn’t difficult for the player to know exactly who means, and when he is shown a picture of Tingle, the man will reward the player for making the connection. This is a perfect example that:

- NPCs can have relationships with each other.

Take it further than the obvious trading sequence: the more the NPCs are familiar with each other, the more the world feels interconnected and realistic. Let the characters be aware of each other—let them have friends and enemies, family members, co-workers. If the player can talk to an NPC and then think “so this guy has a crush on the lady who runs the potion shop”, then you’ve established a connection—not just between those two NPCs, but with the player as well. It opens up tremendous opportunities for minigames and side-quests, but even just including references in the NPC’s dialogue is often enough to give them memorable depth.

Yeto and Yeta appeared as central figures in Twilight Princess‘s most unique dungeon, the Snowpeak Ruins. The inhabit the dungeon—it’s their mansion, and Yeto is cooking soup and lets you replenish your life by drinking some (adding more complexity, there are no recovery hearts in the dungeon because the player is able to recover in this way). But in addition to that, his wife attempts to help the player by telling him the locations of different treasures in the dungeon. And at the end of the dungeon, she is revealed to be possessed and transforms into the boss. These characters show that:

- NPCs can exist within dungeons.

And I would like to see a lot more of it! Dungeons are often dark and lonely, but adding some other characters can open up new design opportunities and make the entire dungeon experience a lot more interesting. Consider a dungeon where the player has to chase down an enemy, or has to work with a friend. The more interactivity in your game, the better. And giving life to NPCs is a great way to to that!

If you’ve played Majora’s Mask, then you remember Kafei. He’s the subject of the game’s largest side-quest, and his storyline intertwines with multiple residents of Clock Town. The most memorable part of the entire game for me isn’t the dungeons or the bosses, but the quest to reunite Kafei with his lover Anju. The final moments, where they clutch each other and proclaim their love against the backdrop of the apocalypse—is beautiful.

Majora’s Mask has a unique three-day cycle—and at different points within those three days, Kafei can be found in different areas. At one point, the player must meet Kafei at a thief’s secret lair. The most memorable part of the Kafei sidequest is that he holds the unique position in the Zelda series of being a playable character. Kafei takes you all over the place:

- NPCs can move.

And I’m not talking about walking in little random circles in a village. Let the NPCs be mobile. If your NPC is recognizeable in appearance and personality, then he doesn’t need to be tied down to a single place. As his story progresses, let the hero encounter him in multiple areas. Remember that your world is populated, that these characters are not just scenery. They have motivations, they have ambitions, they have goals.

They have lives.