Yo. Let’s talk about resources.

And I’m not talking about resources on the developer’s end. We’re not talking about the graphics you’re creating for your project, or your computer power, or any of that stuff. Oh no—we’re talking about in-game resources. The resources that your player has to work with while playing your game. Elements of gameplay that you, as the game designer, have to put some serious thought into.

Dictionary definition: “A stock or supply of money, materials, staff, and other assets that can be drawn on by a person or organization…”

Taking that definition over into video games, I’d say that a resource is a stock or supply of something that can be drawn on by the player. Of course, that definition leads to two obvious questions. One: what is the something? Two: why would the player draw on these resources?

Well, that’s what this article’s about.

Why Resources?

Why are we talking about resources in the first place? What makes the subject worthy of an article?

First off, pretty much every game makes use of resources in some way or another. Even if the player isn’t actively managing his items or stat points, it’s likely that some aspect of the game is about converting some sort of resource into an advantage. Secondly, it seems like the implementation and balance of in-game resources is something that a lot of designers/developers don’t pay enough attention to. It’s easy for a game to feel like something is fundamentally off when it comes to balancing—and when it’s hard to figure out what exactly that something is, it usually comes down to a problem with the game’s resource systems.

Some games make more use of resources than others. And note that it’s not limited to RPGs, but games of all sorts of genres. In one game, the player might not spend any time at all thinking about how he uses the resources available to him. In another, resources are crucial to the gameplay. A platformer like Mario Galaxy might only make use of collectibles in order to open up new areas, where games like Starcraft or Magic: The Gathering are all about maximizing your resources.

Whichever approach you take, it’s important to put at least some thought into how your game handles these resources. If your game is a strategy game, or an RPG, then you’ll need to spend a lot of time working out just how to balance all the possible resource conversions available to the player.

That’s a key idea: conversion. A resource’s worth is directly related to how the player converts it into something else useful to him. For the most part, the resource will be converted into some way that helps the player proceed: like collecting enough stars to open a door, or earning enough skill points to allocate upgrades to a character’s stats. In plenty of cases, particularly in games that are more based around strategy, the player might be converting one type of resource into another. Later on, I’ll go a little more in-depth in the idea of resource conversion.

First, I want to talk about two major different types of resources that you might incorporate into your game.

“Physical” Resources

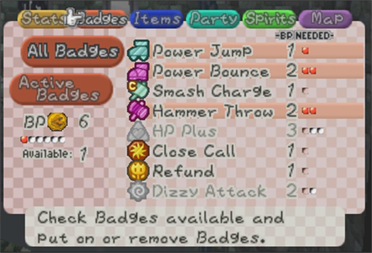

The first type of resource that I want to talk about are the “physical” resources—aka things that the game makes obvious to players are resources. I call them “physical” because these are the kinds of resources that are specifically represented in the game. The player sees them and manages them: their presence is clear and obvious, tangible for the player.

Some common types of physical resources include:

- Currency (Gold)

- Items/Powerups

- Skill/Magic Points

- Collectibles

- Inventory Slots

- Lives (1-Ups)

These are resources that the player earns throughout the game—and the player will need to utilize them in order to overcome the challenges that the game presents. Typically, the more of a certain resource the player has, the bigger advantage he has in the game.

Limits are also resources. Consider inventory thresholds, or equipment slots. In an RPG, you might be able to equip a cool fire skill onto one character. But if you do that, then that slot is filled and you can’t also give him that cool ice skill—it has to go to someone else. This gives the player a sense of creative management that, when handled correctly, can add a lot of depth and fun to a game.

Some of these physical resources will be “pool” type resources. Rather than something that the player collects in the game, it’s something that the player uses through depletion. The best example: in typical RPGs, a character’s MP is also a type of pool resource. In pretty much any game, the player’s life points (life bar, HP, etc) is also pool resource. The maximum size of that pool might change over the course of the game, but the functionality is the same: instead of collecting and building that resource, the player has a default amount and draws from it.

Here’s an interesting experiment: think about different kinds of resources in your game, and how would the gameplay be altered if that resource were to be a pool resource or not. For example, imagine an RPG where the characters don’t have MP, but instead can only use skills by using items the player has acquired. Or the other way: a game where instead of collecting money, the player starts each in-game day with a certain amount of money, has access to that amount for that day, but it refills the next day—like a budget. It’s an interesting exercise to examine how you implement physical resources into your game, and might lead you to discovering a cool new mechanic that makes your gameplay really unique.

“Invisible” Resources

Unlike the physical resources, “invisible” resources aren’t immediately evident to the player. When the player sees that he needs to collect X gold in order to buy a weapon, that’s an obvious physical resource. But the invisible resources are typically build into the gameplay in a way where the average player won’t even realize that it’s a resource.

The best, and most common, example of an invisible resource is time.

Consider a turn-based RPG. While a novice player might not recognize it, each turn itself is a valuable resource—maybe the most valuable resource you have in a battle. Ever hear that saying, “the best defense is a good offense”? There’s a reason for that—if your enemy is dead, then they can’t hurt you. A single turn has a lot of value for that very reason: the player who maximizes each turn will have better success at the game. That’s why I encourage designers to make status effects and buffs/debuffs really matter. If the amount of overall benefit from a special effect ends up being less than simply attacking, then it’s not worth using up a turn on that effect. The player who makes the most out of every turn is maximizing the invisible resource of time.

Here’s another example. In Magic: The Gathering, the typical minimum deck size is 60 or 40 (depending on format). They important word there is minimum: really, a deck can have as many cards as the player wants. Good players, however, stick to that minimum. Playing a deck with more cards than the minimum is disadvantageous: you end up diluting your deck with extra cards, rather than getting the most out of it by only using the best cards available for your strategy. It’s a trade-off: if you want to have more options, you can go over the minimum, but the overall power level and consistency of the deck will be diminished. In other words, you’re not maximizing the resource of your card slots.

Within a game of Magic, the cards themselves become physical resources. But in deck construction, you have the invisible resource of the size of your deck, and how you use that resource is up to you.

One of the biggest difference between physical and invisible resources is that the beginner, or casual, player will likely not recognize the value of the invisible resource. It’s common for the beginning Magic player to play decks that have more cards than the minimum, because they see it as giving them more physical resources (cards) in the game. But the advanced player understands that the card slots themselves might be a more valuable resource in the big picture.

If you are able to craft an interesting balance between physical and invisible resources in your game, your gameplay will have more depth. The best games provide gameplay and challenges for players of different levels and skillsets.

Whoops

This article’s a lot longer than I’d planned (this seems to happen quite a lot). Looks like this is gonna be another two-parter. In the next article, I’m going to dive deeper into the topic of resources: we’re going to talk about implementing them into your game, and how to ensure that everything is balanced. And most importantly, how to ensure that the player has fun while managing resources.