One of the things that I’m proud of is that I’m relatively quick when it comes to pixel art. Sure, most of that come from experience. But a lot of it has to do with my process. It’s especially useful for working on large-scale projects, such as RPGs, which can very quickly become overwhelming. Doing all of the graphics for a large RPG (or even doing a lot of them, like all the characters or all the tiles but not both) can be daunting. Today I’m going to teach you some good habits and some bad habits that will help you manage your time in ways to maximize your pixel art output.

Note that this article isn’t going to be like my other pixel art tutorials. Instead of discussing the pixel process, we’re going to look at some tricks that I use to keep myself productive and not get intimidated by large-scale projects. Be aware that knowledge of pixel art is required before you can expect to start pumping out graphics at a quick rate, so follow through on my other tutorials before diving into pushing yourself for speed. Get the techniques down first. Still, if you have some experience already, hopefully you’ll find these things useful.

Know Your Tools

Maybe this one goes without saying, but I don’t want to not mention it at all. There are a variety of programs useful for creating art. Personally, I use a combination of GraphicsGale, Photoshop and Microsoft Paint (yup, Paint). You can use whatever programs and tools you are comfortable with, but the key is to get comfortable with them. Using your tools should be second nature to you.

If you need to, take the time to search online for some tutorials for the program of your choice. Youtube has plenty of tutorials for GraphicsGale, Photoshop, and practically anything else you could use. It’s worth it to invest the time up-front into becoming familiar with your tools, so that when it’s time to put pixels next to each other, your workspace doesn’t get in the way of your artistic flow.

Re-useable Workflow

Save everything. Even—especially—those little pieces that you find yourself remaking. I have a hierarchy of sorts when making charactersheets. I start with the most generic, then work outwards by continuing to edit it further. Save each stage along the way; you might use them for something. Here’s an example:

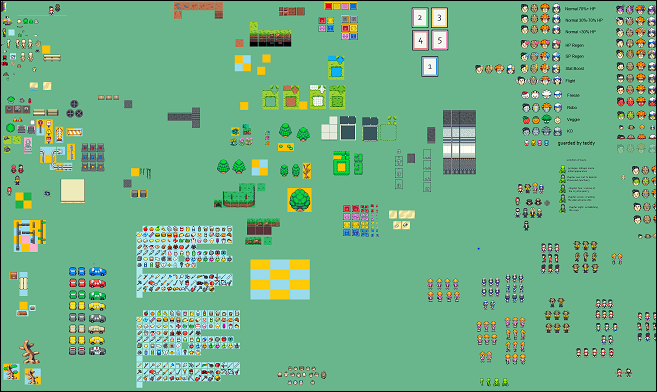

I keep a huge scrap sheet full of pieces like this. It’s basically a big compilation of all the stuff that can be re-used. Lots of it is earlier versions of finalized graphics.

By keeping sheets like this, I rarely have to remake something. It’s especially useful for animation, when I find myself distorting sprites—and knowing that I have the original version saved on the sheet. It’s also super helpful when it comes to making tiles, since many tiles will be edits/recolors of the base versions.

You don’t need to keep a sheet like mine—this was just an example of what I do. You could arrange your scraps any way you want—maybe a separate file for each character, or a bunch of files organized in folders—or maybe one document with a bunch of layers. Whatever is the best for you. The basic idea here that I want to stress is that everything can be useful later on, and when tackling a large-scale project like an RPG, it can save you a lot of time if you don’t delete everything.

Finding Extra Time

Ultimately, the best tip I can give you is to capitalize on your time. You’d be surprised how many hours a week I spend working on pixel art (and other art, and writing, etc); it’d be even more surprising to know that most of these hours don’t come in full hour chunks, but from little extra minutes here and there.

When you have five minutes to spend waiting for your microwaved meal to cook, dash back to the computer and spend them working on your graphics. If you play an online game, and you have a minute to wait for everyone to get ready for the round, you can slap some pixels together. I play a lot of Hearthstone, and I work on my art while my opponent takes his turn. Little chunks like this add up over the day—or the week—or the month. You’ll find that you’ll finish a piece and hardly even realize you were working on it.

If you’re serious about becoming more productive with your time (and not just for art, but anything), consider getting at least two monitors. I have three and I imagine there’d be diminishing returns beyond that, but going from one monitor to two will be a massive boost to your productivity. Leave your current project open on one screen while you do stuff on the other—you’ll find yourself idly working on your art without even realizing it.

Bad Habits and Shortcuts

Now for the potentially controversial parts. ;)

There are some things that a lot of pixel artists will look down on: excessive copy/pasting, recoloring, using “dirty tools”, etc. There’s a good reason why people will tell you to avoid them: they generally lead to lower-quality art. But there’s also a reason that people use these things: they save time.

- Copy/pasting is something that people will tell you to avoid when animating. Generally, animations end up more visually impressive when you redraw every frame. But when you’re working on something large-scale, sometimes you just need to save some time. Gotta make that walk cycle for yet another NPC? Just copy and paste the idle frame and shift around the arms and legs. I wouldn’t do that for a major character, but unless it stands out as being awkward, people won’t think twice about the NPC. Similarly, keeping your NPCs symetrical can save a lot of time. You can copy/paste and then flip your sprites and save tons of time.

- Recoloring is often thought of as a big no-no. But as long as your new colors look good, it can save you a lot of time. Plenty of the classic RPGs used recolored sprites. Two identical NPCs can look vastly different when they have different colors for their hair and outfits. Or you can get a variety of house tiles by changing the color of one house’s roof. As long as you put in the time to make the original look good, recoloring your art can give you more to work with then it’s time to put your game together.

- What are “dirty tools“? The exact definition depends on whose speaking, but generally, it’s a dirty tool if you aren’t manually placing colors on the canvas. Gradients, smudges, automatic anti-aliasing, layer effects, etc, are all “dirty”. While these things I would agree will usually mess up your pixel art, other things are often considered “dirty” but can be legitimate time savers. Using Photoshop to rotate, stretch or scale your art can be fine, so long as you manually clean up the distortion.

The thing about bad habits is that they’re not always bad. It’s a matter of learning when and how to apply these things; they go from being bad habits to useful tools that you can employ among the other skills in your artistic arsenal.

Recognizing “Good Enough”

If we all had infinite time and no deadlines, I’m sure we’d all make amazing wonderful art. But that isn’t the world we live in (and I don’t think I’d want to!).

A project will never be finished if you spend six months trying to make a single tile absolutely flawless. Spoiler: it’ll never be flawless. As you work on something, you naturally get better. You learn more, and you’ll naturally want to revisit your old stuff and bring it up to your new standards.

This is a trap. Believe me—I’ve been there. Many, many projects have died for this very reason. You make a bunch of graphics, but then you look back at them and think “I can do better—let’s redo them.” You end up wasting a lot of time, and likely lose your drive for the entire project.

One of the hardest things that I’ve done—in terms of advancing my skills in pixel art—is learning when a piece is “good enough” and it’s time to move on to the next one. Sure, a sprite might be a little better if you take the extra time to add that little bit of detail, or that extra chunk of animation. But in the time you’re doing that, you could have made two more sprites.

Refining a sprite often takes more time than making it to begin with. On some sprites, it’s worth it. For example: the hero will want a lot of attention, since the player’s going to be staring at it for the entire game. But for most of your sprites and tiles, it’s not worth the time to push them too far. They can always be better—but they usually don’t need to be. The person playing your game isn’t going to think about what you could have done.

Plus, remember that you can always come back to something if it’s giving you a particularly difficult time. Leave it as it is, and work on something else. Clear your mind. Then come back to the piece that’s giving you trouble.

I’ve finally gotten the hang of this—as painful as it might be—and I’m making progress like I’ve never made before. The key is to keep moving forward.

Next: Basics of Animation