Dungeons! Any RPG would be incomplete without them. The dungeons in your game are where the majority of the gameplay will take place—your dungeons are the meat of your game. You can expect your players to spend a lot of time—and a lot of thought—in your dungeons, so it’s important to make them stand out.

What is a dungeon? A dungeon is an area of the game that provides danger and challenge for the player. Typically, RPGs are split up into two types of areas: towns and dungeons. Towns are places where the player can relax and heal; where he can comfortably explore and upgrade his characters: towns are typically the resting places between dungeons. But just like town areas don’t need to be towns—a dungeon doesn’t have to be a temple or a cave—any setting you can imagine can be a dungeon area—as long as it provides the potential for danger. These area definitions are based on gameplay function.

So let’s get creative with our dungeons.

Setting and Theme

Often, the first idea that a game designer comes up with for a dungeon is the setting. A cave dungeon, a dark castle, a pyramid maze. This is a good starting place, but unfortunately it usually comes out of forced necessity (“I need a dungeon in my desert region!”) This line of thinking leads to the same tired dungeons that we’ve seen a hundred times before.

Don’t misunderstand—there’s nothing inherently wrong with putting obvious dungeons in the obvious places; the important part (as always) comes down to the execution. This is why I encourage you to think of the dungeon’s theme before you worry about the dungeon’s setting.

The theme of your dungeon is more about the tone and feel than it is about the actual location. And when done right, it will naturally tie into the gameplay gimmick of the dungeon. Giving your dungeon its own theme will allow it to stand out as a memorable location on its own; rather than being something as simple as “the cave in the mountains”.

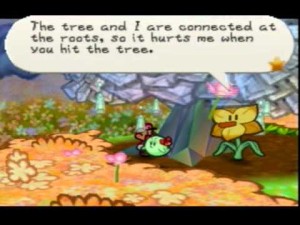

Unlike other dungeons, Flower Fields in the original Paper Mario was unique in that it was an outside area with lots of interactive characters.

But what exactly do I mean by “theme”? Honestly, it could be anything. Think about your game world and the story, and what elements will lead to a strong dungeon design? Maybe there are elements of your world’s cultural beliefs that can be extracted and turned into a unique theme: a multi-floor tower based on a religion’s attempt to reach the heavens; an ancient network of catacombs that runs from the castle cellar all the way to the walls of the city; a complicated factory that shows off the developing technology of a society. Most dungeons are boring when they are completely natural—it’s hard to come up with good puzzles in such a setting. Who built this area? Why?

Instead of thinking “what makes sense in this region?”, ask yourself “who would create something in this region and why?”

Once you have a strong and specific theme in mind, you can work it into the setting. Let’s take the “reach the heavens” tower as an example: if it’s in a forest, I can imagine massive spires intertwining with treetops. If it’s in the mountains; it could be broken up into multiple connected towers built around the rock formations, each one higher than the last. Or it could be in the middle of a flat prairie, which would turn it into a striking man-made monument that dominates the horizon.

Gimmicks and Goals

What’s the purpose of the dungeon? Why does the player go there? And when he does—what challenges his progression? What makes the dungeon dangerous? Where’s the conflict?

If your dungeon is nothing more than mazes and random encounters, the player’s not going to have a particularly fun or memorable experience. Remember that the dungeons in your game are the places where the player expects to find challenge. The dungeons—more than anywhere else—must include actual gameplay. Wandering around waiting for battles isn’t gameplay (or at least, it isn’t any good). The dungeon needs some sort of puzzle or action element that provides a unique challenge for the player.

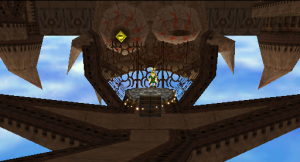

The Stone Tower Temple in Majora’s Mask had a unique and memorable gimmick: the whole dungeon turned upside-down.

A great way to develop a dungeon’s gimmick is to give your player a goal. There are two primary types of major goals. Some are born of the story and work well to motivate the player: find the legendary crystal, reach the end of the tunnel. Then there are the goals that give the player something to work towards in the dungeon itself: turn off all the water valves, destroy the pillars underneath the boss room. If you’re able to come up with a goal that fits both of these roles, and can be incorporated into both the story and the gameplay—escape from a pursuing monster, free a prisoner from a prison—you have a very strong base for a memorable dungeon.

Ensure that the goal is clear to the player (and yourself as the designer), and build each room and puzzle within the dungeon to lead to that goal. It’s certainly possible to have multiple goals; especially if they are nested within each other. For example—the overall goal of a dungeon may be grab a magic crystal; but in order to do that, the player’s mechanical goal is to find a way to open the sealed door.

Once you’ve established the goal of your dungeon, you can begin to think about how the player should achieve that goal—or more accurately; how to make it challenging for him to achieve that goal. This is where we can come up with a strong gimmick—a gameplay element that the player masters throughout the course of the dungeon. A good gimmick is centered around a core mechanic or two.

Consider a single puzzle element—the classic RPG example of block-pushing puzzles. Multiple puzzles can be created using the same mechanic. If your dungeon’s gimmick is based around these sorts of puzzles, then they will get larger and more complex as the dungeon goes on. Even more—you can introduce other elements along the way that can make for more challenging puzzles yet remain consistent with the overall gimmick and goal of your dungeon.

The mechanics in Portal 2 were introduced gradually, letting the player get used to them before the mind-bending puzzles late in the game.

Train your player. Early puzzles should let the player discover how game mechanics work, and end puzzles should feel like challenges that test that knowledge. Your dungeon should have a “puzzle boss” at the end, a major puzzle that incorporates elements of everything that has come before within that dungeon. And when designed well, this final puzzle will directly lead to the player accomplishing the dungeon’s mechanical goal.

That way, the player feels good about himself when he wins. Challenge the player so that he feels good when he overcomes the challenge—that’s what game design is all about.

A lot of the ideas discussed in this article are also covered in brickroad’s awesome article about dungeon theory. Check it out on RPGMaker.net.